I became a book cataloguer in December 1974 at the age of twenty-six. That, at least, is the date of my first catalogue — a twelve-page listing of books on London, just forty items, priced between £10 and £350, and issued just before Christmas. A painfully simple production, typed up on a clanky and sticky-keyed manual typewriter from notes in a card index, given a few words of title in larger lettering by the use of dry-transfer Letraset, and taken to one of the new photocopier shops which were beginning to appear for copies to be run off and stapled together.

As I recall, I typed the whole thing up in a single night and added the Letraset towards dawn, although given my general ham-fistedness I may have got someone else to do that fiddly last bit. I braced myself to open it again after all these years, fully prepared for a gale of embarrassment at its naivety and amateurism. But actually, for a first attempt, it is not too bad. I had received no tuition at all and was simply aping the sort of thing I had encountered on catalogues from other booksellers and auctioneers. But how hard could it be? Most of the information you need is right there in big letters at the front of the book.

It would not pass muster now. The organization of the material was patchy, inconsistent and haphazard. The only concession to bibliographical orthodoxy lay in a handful of references to John P. Anderson’s Book of British Topography — an ancient 1881 catalogue of the topographical works in the British Museum. I was clearly struggling for the appropriate terminology in places, but, for all that, it gets the essentials across. It was honest and enthusiastic — even confident in places — and I was greatly surprised to find that I had already adopted some characteristic traits, habits and turns of phrase which have endured down the years.

I was also surprised at the quality of the books. Those early London books were rather easier to come by then, of course, but there were copies of Brydall’s Camera Regis (1676), Delaune’s Angliæ Metropolis (1690), and Howell’s Londinopolis (1657), as well as the grand eighteenth-century folios of Stow, Maitland and Thornton, and some genuinely out-of-the-way nineteenth-century material.

What strikes me most, however, is that the narrative I thought I was writing — a record of the gradual evolution of a mature cataloguing style — is actually more the story of a sequence of adaptations to the exigencies of circumstance and the available technology. These old catalogues are the way they are because of what was needful, what was possible, and what was affordable at the time.

That first catalogue was a toe-in-the-water kind of exercise, but there were already larger plans. Flagged up on the back cover was the promise of a full-length catalogue of modern first editions, etc. — my second catalogue, forty-eight-pages, published in the summer of 1975 and listing a thousand books. Prices ranged from £2 to £150 (a 1922 Ulysses), with most in the under £10 bracket — but that was a bracket which then included eight first editions by T. S. Eliot, three by Ian Fleming (three James Bonds, all in dust-jackets, £2.50 each), six by Thomas Hardy, four by Robert Louis Stevenson, five each from Evelyn Waugh and H. G. Wells, and four by Virginia Woolf. “Modern” we took to mean post-1800 (a rather outmoded notion even then), so Byron, Dickens, Thackeray, Trollope, and a host of lesser nineteenth-century names were also represented. As a simple point of reference, £2.50 was then a typical price for new hardback fiction — the price at which Ian McEwan’s first book, First Love, Last Rites, was published that same year.

The length of the catalogue — a thousand items — was the product of necessity. I had by now a huge number of books: those originally taken over from Jones and Nash — themselves enough to fill the shelves of the shop several times over, the surplus now housed in a basement in Hoxton; another shopful from the house in Wimbledon; a couple of interesting private collections; and all the books from several further large hoards that Jones and Nash had squirreled away over the years in various suburban hideaways and only now brought to light.

We were going to have to reach out well beyond our local City of London clientele to find homes for all of these. And as we had nothing much in the way of a mailing list, we were going to need to sell to the trade. In addition, a catalogue of this length would have to be properly typeset and printed — an expensive business — the number of pages had to be kept to a minimum.

Those were the factors which dictated the spare nature of the cataloguing — books crammed in at over twenty to the page. But learning to be succinct is not the worst place to begin as a cataloguer. An opening statement gave an indication of detail routinely omitted: “Unless otherwise stated, all the books described in this catalogue are first editions, in the original cloth or boards, octavo or crown octavo in size, published in London and in good second-hand condition”.

Quite what the distinction was that we were making between octavo and crown octavo, I have no idea. I have an uneasy feeling we may simply have cribbed the formula from someone else, but even so, it does not fully indicate all that was to be left out: also omitted were details of publishers (unless of particular interest), details of pagination, and notes on content. Inscriptions were only recorded if by the author or by someone of note, unless perhaps they were uncommonly unsightly. Bookplates were mentioned but rarely identified.

Descriptions of condition were terse — and often harsh. We had not yet learned to be fair to ourselves as well as to our buyers, but then again, no-one ever complained that the books were in better condition than they were expecting — and condition in any case mattered far less in the 1970s. Although there were many more bookshops around, the odds of chancing across a particular book were not greatly in your favour. The annual cycle of domestic bookfairs was barely in its infancy, the internet still years from fruition. No opportunity to pick and choose — you were, by and large, grateful to find a copy at all. Even the absence of a dust-jacket was not necessarily crucial, and I am quite unable to recall anyone going to the trouble of recording whether a jacket was price-clipped or not.

But for all its lack of sophistication, the formula worked. The telephone did not stop ringing for days with multiple orders and it set the pattern for an annual series of similar productions — a thousand items, attention-seeking cover illustrations of the what-on-earth-is-going-on school, as decreed by Pamela — and a very wide mix of material.

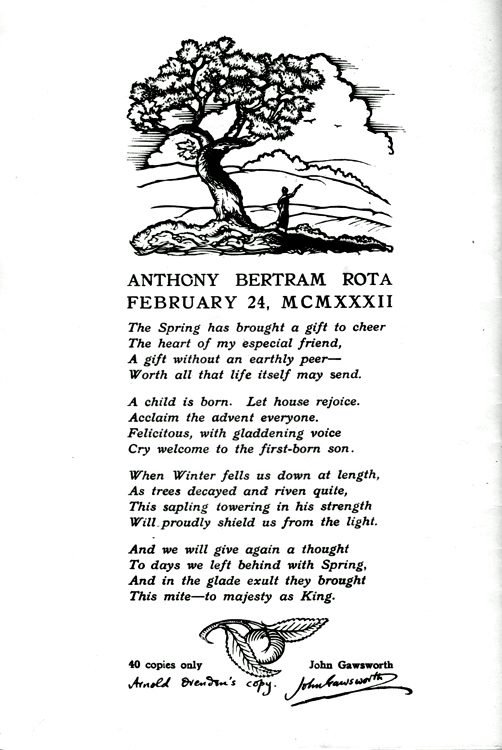

Very cheekily, rather naughtily, we included a single illustration in 1975. It was a full-page reproduction of a nativity poem from that “excessively minor poet” known as “John Gawsworth” (Terence Ian Fytton Armstrong) — a poem in honour of the birth in 1932 of one Anthony Bertram Rota — the bookseller Anthony Rota (Bertram Rota Ltd.), then in 1975 indisputably the leading London dealer in modern firsts. His obituary in The Guardian quoted a colleague as saying, “if booksellers were priests once, Anthony Rota was pope”. I regretted the decision to include the illustration even before the catalogue came back from the printers — gauche and unnecessary — but this was essentially a trade list, we knew it would amuse our fellow booksellers and get the catalogue talked about.

Anthony rose magisterially above it. He telephoned to say, somewhat drily, but certainly sincerely, “I really must congratulate you on the breadth and scope of your catalogue — most impressive”. I did not know him personally then, we only became firm friends after finding ourselves cloistered together for several days in a remote corner of a bookfair in Tokyo in 1990 — but it was a message that meant the world to me at the time — a message of acceptance, acknowledgement and approval from the pinnacle of the London trade.

I am still hazy about the difference between octavo and crown octavo…..

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. I am not surprised, and you will not be alone. I think what we were trying to say was that although most of the books conformed to that quite broad range of sizes associated with the term octavo (8vo), many were towards the smaller end of that spectrum, e.g. the crown octavo.

In strict bibliographical terms, octavo does not refer to size at all, but to format. It means that the book is made up of individual printed sheets, each folded three times, to produce a gathering of eight leaves (hence the name) – sixteen pages, of which at least the first was generally marked by a small letter at the foot, which acted as a guide to ensure both that the sheet was correctly folded, and that the folded sheets were assembled within the book in the right order.

The finished size of the book was dictated by the starting size of the original sheet. A traditional British crown sheet of twenty inches by fifteen (50.8 x 38.1cm), when folded into octavo format, would produce a leaf size (if untrimmed) of seven-and-a-half inches by five (19.05 x 12.7cm) – a crown octavo. To name only the most common sheet sizes, foolscap sheets were a little smaller, while post sheets (in Britain, but not necessarily in America) were a little larger. Demy, medium, and royal sheets were larger still – the last (a royal 8vo) giving an untrimmed leaf size of ten inches by six-and-a-quarter (25.4 x 15.88cm). Less often encountered, but progressively larger again, were sheets in super royal, elephant, double crown, imperial and atlas. There is a simple reference chart of formats and sheet sizes in my “Cataloguing for Booksellers” (https://www.ashrare.com/cataloguing.html).

I hope this helps dispel the haziness. All best wishes, Laurence.

LikeLike

Excellent – you have made my morning. I will look out your cataloguing guide.

LikeLiked by 1 person