Have I not here the best cards for the game,

To win this easy match play’d for a crown?

(Shakespeare, King John).

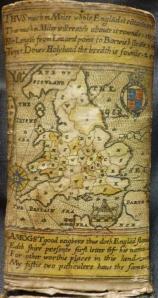

I recently mentioned in passing a very early map of London engraved on a playing-card. Here, courtesy of the British Museum, it is (click to enlarge) – the additional London card from the William Bowes set of playing-cards published in 1590. I say additional in that it is not one of the regular fifty-two numbered suit-cards, which feature maps of the counties, but one of the accompanying historical cards (there is also an explanatory card on London’s history), rarely present in the handful of surviving sets. The discussion began in the recent acquisition by the British Library of a beautiful hand-coloured set (without the London cards), which you can read all about in Tom Harper’s post on the BL Magnificent Maps blog at http://britishlibrary.typepad.co.uk/magnificentmaps/2014/10/new-acquisition-the-bowes-playing-cards-of-1590.html.

The playing-card map is surprisingly not listed in James Howgego’s usually authoritative “Printed Maps of London”, which is perhaps why it remains relatively little known, but after some deliberation and further correspondence, we concluded that it is indeed the earliest extant map of London actually engraved and produced in London: the handful of earlier maps comprise one of which only portions survive (and may well have been produced abroad), one which survives only in much later impressions, and two produced overseas.

It’s not a magnificent map in itself – tiny, lacking in detail and comparatively unsophisticated – except that the cards were engraved by Augustine Ryther, whose name appears in truncated form in minuscule letters intertwined with the pair of compasses on the general map of England and Wales. Ryther himself was very far from lacking in sophistication: he was one of the most interesting of Shakespeare’s contemporaries and deserves to be better known.

He is remembered as an engraver, responsible for five of the maps in Christopher Saxton’s atlas of England and Wales (1574-1579), our first national atlas and the largest and most complex book yet produced in England. His work included the general map of England and Wales on which his name appears as “Augustine Ryther Anglus” – “Augustine Ryther, an Englishman” – a fact odd and unusual enough, given the paucity of engravers in Elizabethan England, for him to remark on it – he was the only one of the Saxton engravers certainly English. Despite the lack of an English engraving tradition, his maps, as Sidney Colvin noted long ago, are “distinctly the best in the book … the neatest and most precise in cutting and lettering, the most graceful and inventive”.

Ryther subsequently engraved several maps for the London edition of Lucas Janszoon Waghenaer, “The Mariners Mirrour” (1588), the first maritime atlas produced in England, working in this capacity alongside both Theodore de Bry (in England briefly before settling at Frankfurt) and Jodocus Hondius – men who went on to found two of the greatest map-publishing houses in Europe. Ryther then produced his own atlas, “Expeditionis Hispanorum in Angliam Vera Descriptio” (1590), comprising eleven folio maps from designs by Robert Adams, illustrating the harrying of the Spanish Armada and published together with a narrative by Petruccio Ubaldini. This was the third and last atlas produced in England in the sixteenth century (and the first published without explicit government backing): and Ryther is their sole connecting link.

Ryther subsequently engraved several maps for the London edition of Lucas Janszoon Waghenaer, “The Mariners Mirrour” (1588), the first maritime atlas produced in England, working in this capacity alongside both Theodore de Bry (in England briefly before settling at Frankfurt) and Jodocus Hondius – men who went on to found two of the greatest map-publishing houses in Europe. Ryther then produced his own atlas, “Expeditionis Hispanorum in Angliam Vera Descriptio” (1590), comprising eleven folio maps from designs by Robert Adams, illustrating the harrying of the Spanish Armada and published together with a narrative by Petruccio Ubaldini. This was the third and last atlas produced in England in the sixteenth century (and the first published without explicit government backing): and Ryther is their sole connecting link.

He was also responsible for engraving the beautiful eight-sheet Ralph Agas wall-map of Oxford (1588), surviving in a unique copy, and the equally rare and impressive John Hamond wall-map of Cambridge (1592). He is also generally credited with engraving Saxton’s wall-map of England and Wales (1583) and he appears to have acquired the Saxton county plates, probably when Saxton’s privilege expired in 1587, the maps sometimes found bound together with his Armada maps on identical paper.

“Expeditionis Hispanorum in Angliam Vera Descriptio”, 1590. © The Trustees of the British Museum. 1888,1221.8.7.

In collaboration with the celebrated mathematician Thomas Hood, he engraved two planispheres (the first produced in England) to accompany Hood’s “The Use of the Celestial Globe in Plano, Set Foorth in Two Hemispheres” (1590), as well as a fine chart of the North Atlantic (1592) – “a beautiful example of what must be the first printed English plane chart designed expressly for navigation and instruction” (David W. Waters).

Theodolite by Augustine Ryther, 1590. © 2010 Museo Galileo – Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza, Firenze.

It is difficult to overstate Ryther’s importance to the history of English cartography, but he had a yet greater claim to fame. He was also a maker of scientific instruments and, although few examples survive, a very fine one. Here is his theodolite of 1590, a key instrument in surveying and perhaps a clue as to how advanced Saxton’s surveying technique may have been. As an instrument-maker Ryther stands literally at the head of his profession: his is the first and founding name in an unbroken master-apprentice chain of unparalleled distinction, leading directly on through his apprentice Charles Whitwell to some of the greatest names that craft has ever produced – Elias Allen, Edmund Culpeper, and the famous families of Adams and Troughton.

Biographical information is scant. Ryther was reported by the local historian Ralph Thoresby to have been born in Leeds – by no means unlikely as the name Ryther is a Yorkshire one (and he certainly engraved the Saxton map of Yorkshire), although this remains to be verified. It is conjectured (the similarity between their theodolites is striking) that he was a pupil of Humphrey Cole, himself a northerner and superb instrument-maker. In 1581 (recorded as Augustin Ryder) he married Alice Maskall, a widow, at the London church of St. Andrew Undershaft. He was a member of the Worshipful Company of Grocers in the City of London, and in 1590 described himself as still “a yoong beginner”. The only address we have dates from that same year, “A little from Leadenhall next to the signe of the Tower” (it was at the Leadenhall that Hood gave his lectures on navigation).

Ryther was buried at St. Andrew Undershaft on 30th August 1593 – one of five burials that same day in one small parish, perhaps suggesting the outbreak of some virulent pestilence. Earlier identifications with “this poore Gent. Mr Ryther”, imprisoned in the Fleet in 1594, are now known to be erroneous. Widowed once more, Alice Ryther remarried Richard Dawberry at the same local church on 21st April 1595 – and there the biographical trail ends, except that Ryther’s legacy lived on.

The Cittie of London. Later state, with compass rose, ca. 1640. © The British Library Board. Maps Crace Port. 1.32.

Part of that legacy is another map of London long ascribed to Ryther: a considerably larger map on a scale of about nine inches to the mile, titled “The Cittie of London”, and known in a number of variant states. The attribution to Ryther goes back at least as far as the compilation of the catalogue of the Frederick Crace collection of London material in 1879, when the map was ascribed a date of 1604. The later of the two Crace copies, now in the British Library and illustrated here, has Ryther’s name neatly pencilled near the lower border, although whether this is the source of the attribution or the consequence of it is not clear.

It cannot be by Ryther or dated to 1604 – at least in the forms in which we know it. Ryther died in 1593 and the internal evidence of the map, even in its earliest state, suggests that it dates from some forty years later. There are other indications, but the most telling is that the map (with no evidence of reworking in the earliest state) shows a gap where the buildings north of London Bridge were destroyed by fire in 1632. Nor is it apparently an English map: the earliest variant states quite plainly, “to be sould at Amsterdam by Cornelis Danckerts grauer of Maps”.

Since the attribution to Ryther appears to be faulty, the general supposition has been that the map is merely a Dutch copy of something English and for that reason it has largely been disregarded in discussions of London mapping. The map is, however, barring the little inset on the John Speed map of Middlesex, the only surviving printed map of London from the whole of first half of the seventeenth century. It deserves rather more attention than it has received. It is not inaccurate, as has sometimes been said. The lesser buildings are stylised, the clutter behind the street frontages largely unexplored, the street-widths much exaggerated for clarity of lettering and ease of wayfinding (just as in a modern “A-Z”), but this does not make it inaccurate. You could still easily find your way round the City of London with this. It’s an important map of pre Civil War London.

Although ostensibly Dutch, as Ashley Baynton-Williams points out, “the title, imprint and toponymy are all in English”. It does not look or feel like a Dutch map and Danckerts does not even claim to have engraved it. There is no real doubt that the later states were published in England. Howgego identified three of these later states, Ashley has uncovered two more, and in looking at the various examples in the British Library the other day, we now seem to have found another one. The map was clearly kept up to date in London throughout most of its life, with details erased and inserted, and numerous street names added.

The Cittie of London. Earlier state, with the Danckerts imprint. ca, 1633. © The British Library Board. Maps Crace Port. 1.31.

The suspicion is that the map was in reality an English publication all along. But why should a London publisher disguise an English map of London to look like a Dutch one? I think we need look no further than the vagaries of the licensing of English publications at this time. Someone like George Humble, publisher of the Speed maps, stocking an unrivalled range of cartographic material but without a full-size map of London, would have had particular problems in publishing a London map under his own imprint. In 1618, the surveyor Aaron Rathborne had been granted a twenty-one year privilege for a projected series of town-plans of English cities. In effect, he had been given a monopoly on producing town-plans and although he failed to produce any, there was a specific bar on anyone else doing so. I think we can understand the temptation for a London mapseller to resort to subterfuge. It is noticeable that the Danckerts legend was dropped from later states of the map at about the same time as the patent expired.

© The Trustees of the British Museum. 1895,1031.481.

Engraved title-page to Aaron Rathborne, “The Surveyor”, London, 1616.

Rathborne may himself have been caught up in an overlapping second patent granted in 1619 – a patent granted for thirty-one years for a bizarre monopoly on printing anything printed on one side of the paper only. This was a patent vigorously contested and equally vigorously defended by the patentees, Thomas Symcock and Roger Wood, both in reality assignees for the principal beneficiary, one Marin de Boisloré, “esquire of the body to his Maiestie” and someone with probably greater clout than Rathborne. Maps were certainly included under this “one-side-only” heading: both Speed and Humble were among those who petitioned the Commons over the matter in 1621. The patentees had the right to impound anything not printed by themselves as well as rights in “taking, seazing, carrying away, defacing and making vnseruiceable, of all such printing presses, roling presses, stamps [plates], and other instruments” which may have been used to print them. This would place any map-publisher in serious jeopardy. The patent was finally annulled in 1631 and it may not be coincidence that the London map appears to have first surfaced shortly afterwards.

Aside from the possibility that the map was a covert English publication all along, there are still unresolved questions. Either it is an original map of the early seventeenth century compiled by some unknown hand, in which case it demands some more detailed attention – or it is a copy of something earlier. As it bears no real resemblance to any of the known earlier maps, in style, extent or scope, the former is perhaps more likely. But the survival rate of these early maps is poor – perhaps there was an original now lost. And perhaps too the Victorian compiler of the Crace catalogue knew more than we do and it is a copy of something by Ryther – possibly a draft left unpublished at his early death or a project left in the hands of his apprentice Charles Whitwell, himself a superb engraver and instrument-maker. Such things are not impossible.

Did Augustine Ryther father any children or do we not know?

LikeLike

He had no children that I am aware of, but records are scant.

LikeLike