I occasionally come across these little mid-nineteenth-century engraved views of London landmarks, measuring about six inches by just over four and half, and published by J. T. Wood. They are generally printed on what I have tended to describe as ‘glazed card’. I have also seen it described as ‘metallic card’, but I now learn that Wood himself called it ‘enamel card’ or ‘enamelled card’, as did the man who made it for him, so there is one correction to the record to be made.

I occasionally come across these little mid-nineteenth-century engraved views of London landmarks, measuring about six inches by just over four and half, and published by J. T. Wood. They are generally printed on what I have tended to describe as ‘glazed card’. I have also seen it described as ‘metallic card’, but I now learn that Wood himself called it ‘enamel card’ or ‘enamelled card’, as did the man who made it for him, so there is one correction to the record to be made.

The subjects are often popular ones, not always restricted to London, the design and engraving highly competent (if no more), and I do not charge a great deal for them, but the cards only sell slowly, if at all. Condition can be problematic: the cards tend to brown or blacken towards the outer edges and often suffer from slight surface abrasion, leading to some weakening and fading of the image. Even where this is not the case, few of my customers appear actively to like them. There is also a difficulty in explaining what they were for. They were obviously separately published and not intended as book illustrations (although sometimes catalogued as if they were).

The subjects are often popular ones, not always restricted to London, the design and engraving highly competent (if no more), and I do not charge a great deal for them, but the cards only sell slowly, if at all. Condition can be problematic: the cards tend to brown or blacken towards the outer edges and often suffer from slight surface abrasion, leading to some weakening and fading of the image. Even where this is not the case, few of my customers appear actively to like them. There is also a difficulty in explaining what they were for. They were obviously separately published and not intended as book illustrations (although sometimes catalogued as if they were).  Wood also produced the same engravings in the form of decorative notepaper, which has an obvious practical purpose – and on the odd occasion you see them in this form you get a better idea of the quality and care of the engraving – but the point of printing them on enamelled card remains elusive. I have heard it suggested that they were intended to be pasted on other things, sewing-boxes and the like, which may be true, but I think they were simply intended as mementoes, or perhaps as what Wood called ‘conversation cards’, most obviously to be stuck in a scrap-books. This is precisely what happened in the case of this view of Westminster Abbey.

Wood also produced the same engravings in the form of decorative notepaper, which has an obvious practical purpose – and on the odd occasion you see them in this form you get a better idea of the quality and care of the engraving – but the point of printing them on enamelled card remains elusive. I have heard it suggested that they were intended to be pasted on other things, sewing-boxes and the like, which may be true, but I think they were simply intended as mementoes, or perhaps as what Wood called ‘conversation cards’, most obviously to be stuck in a scrap-books. This is precisely what happened in the case of this view of Westminster Abbey.

As one might expect, there are good collections of these cards in the Guildhall Library, the British Museum, and elsewhere, but no-one seems to have regarded them highly enough to research Wood himself. It was a recent enquiry from an American archivist which prompted me to dust off some old notes and to delve a little further.

I have not been able to trace the exact record of his birth, but Joseph Thomas Wood was born in Wapping in London’s East End in or about 1811. His rather younger brother, John Andrew Wood, was born in 1823, the names of the Wood parents then recorded as William and Maria, but the interval of time may suggest that Maria was a second wife.

The earliest record of J. T. Wood himself I have traced is his marriage to Sarah Edgington at St. Pancras on 7th April 1833. A son, Joseph Robert, was born in Holborn in 1836, at which time Joseph Thomas Wood was described as a copperplate-printer, evidently his original occupation. He was still so described on the 1841 Census, by which time his brother had become an apprentice at the family home at 9 Curriers’ Hall Court, London Wall. It was also in 1841 that we find his earliest recorded publication, a small broadside printed in gold on black paper, offering A Form of Prayer and Thanksgiving for the birth of the new Prince of Wales, later to become Edward VII. Wood was clearly experimenting both with a burgeoning market in this kind of printed ephemera and with more exotic and fanciful methods of printing. The earliest of the enamel or enamelled cards with London views appeared not long after (there are two examples in the Guildhall Library bearing this early Curriers’ Hall Court address).

In terms of dating his later productions, it may be as well to insert here that by 1845 Wood had moved to 33 Holywell Street, off the Strand, where he remained until probably 1860, with additional premises at 41 Holywell Street from 1854 onwards, but at least by January 1858 his principal address was at 278 Strand. By 1860, probably at the time of the final removal from Holywell Street, he was also occupying 279 and 280 Strand, although he appears only to have advertised these additional premises from 1867 onwards (in the case of 279) and 1871 (in the case of 280). Other addresses occasionally seen in connection with Wood probably relate to ancillary workshop or warehousing facilities.

Experimentation continued: in 1851 he produced a series of views of the Great Exhibition printed in bronze on ‘gelatine’ of various colours – red, blue and green – which I have not seen, but there are examples in the V & A. As well as publishing views and mementoes, Wood was also experimenting in other areas. He published chapbooks and populist part-works in penny numbers, for example Wood’s Frugal Cook. Complete in 12 Penny Nos, advertised in 1852. He acted as an agent for the toy-theatre publishers, producing several toy-theatre plays of his own. And he built up a range of stationery products, many of them intended and advertised for wholesale and export rather than simply retail sale. He offered notepaper; envelopes; foreign fancy prints; tomb cards and tablets; window and show cards; poetry cards (in gold, silver, satin, and gelatine, embossed and perforated, and in envelopes); puzzle, toy and conversation cards; embroidery, knitting and crochet books and patterns; children’s books; almanacks – and of course his views of London on enamelled card, priced at an extraordinarily cheap price one penny each. A penny was worth far more then, but I am still puzzled at how these could have been carefully printed one at a time for this kind of price.

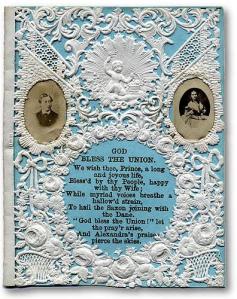

What Wood really became known for was a line of products advertised in Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper (13th August 1854) as ‘Wood’s perforated lace paper and cards’. There are some outstanding examples of these lace-paper designs in the V & A, and Wood expanded his range to include not just stationery but a whole range of other things. Having filed a patent in 1859 for ‘improvements in printing and embossing dies’, in 1861 he took out another for ‘an improvement in open work fabrics, suitable for ladies’ collars, cuffs, and such like articles, and for purposes for which perforated paper and cardboard are employed’. He also registered designs with the Board of Trade under the Ornamental Design Act of 1842 – there are records of forty-five of these between 1854 and 1875 in the National Archives.

In Reynolds’ Newspaper (9th June 1861), by now additionally styling himself the London Lace Paper Company, he advertised ‘Wood’s paper-collars’ (one penny each, nine-pence a dozen), ‘Wood’s lace paper collars for ladies’ (twopence each) and even ‘Wood’s paper dish covers’ (eight-pence each). But his chief line was probably in the production of Valentine cards – intricate, elaborate, overblown, extraordinary and in the full flowering of Victorian taste (there are numerous examples on the Museum of London’s website).

In Reynolds’ Newspaper (9th June 1861), by now additionally styling himself the London Lace Paper Company, he advertised ‘Wood’s paper-collars’ (one penny each, nine-pence a dozen), ‘Wood’s lace paper collars for ladies’ (twopence each) and even ‘Wood’s paper dish covers’ (eight-pence each). But his chief line was probably in the production of Valentine cards – intricate, elaborate, overblown, extraordinary and in the full flowering of Victorian taste (there are numerous examples on the Museum of London’s website).

This was by now big business – Wood was now advertising himself as the largest wholesale manufacturer of plain and fancy stationery in the country.  The London City Press (15th July 1865) reported on the second annual dinner of the employees of Mr. J. T. Wood of the London Lace Paper Company at Rye House. “About ninety sat down to dinner. In response to the toast, ‘Our Employer’, Mr. Wood said it was a day of great pleasure to him, to see so many of his people so happily assembled. The other toasts received hearty and appropriate replies, and after a few excellent songs, the guests went forth to their amusements again”. By 1873 the claim had become that of being ‘the largest Valentine manufactory in the world’ 1873 – and as a token of an international trade, the later little London cards were also given an additional title in French.

The London City Press (15th July 1865) reported on the second annual dinner of the employees of Mr. J. T. Wood of the London Lace Paper Company at Rye House. “About ninety sat down to dinner. In response to the toast, ‘Our Employer’, Mr. Wood said it was a day of great pleasure to him, to see so many of his people so happily assembled. The other toasts received hearty and appropriate replies, and after a few excellent songs, the guests went forth to their amusements again”. By 1873 the claim had become that of being ‘the largest Valentine manufactory in the world’ 1873 – and as a token of an international trade, the later little London cards were also given an additional title in French.

Wood’s son, Joseph Robert Wood, who worked with him and would probably have inherited the business, died in 1868. Wood’s wife, Sarah, died at their home at 33 Claremont Square, Pentonville, after a long illness in the summer of 1870. His brother, John Andrew Wood, who had been with him from the start, died aged fifty-one in 1874. Wood himself died aged sixty-five at a new home known as Thyra House, Alexandra Grove, Finchley, on 16th July 1876.

For all the size of the business, it had lost its momentum. Philip Brown’s London Publishers and Printers c. 1800-1870 records the firm continuing in the Strand to 1885 and at various other addresses on into the twentieth century, but I have been unable to garner anything of its activities after Wood’s death. His will was proved by the surviving executors, William Trevillion of Islington, described as ‘writer and grainer’ – he was originally a house-painter and I think the sense is of a sign-writer – and Henry Burnett of Silver Street, Golden Square, a printer in a moderate way of business. They were probably friends rather than colleagues.

Wood was a wealthy man, his estate valued at something approaching £14,000. There appears to have been some kind of dispute over the will and in 1879 the London Gazette reported that various properties had been ordered by the court to be sold in a case listed as Wood v Trevillion – leaseholds in Stepney and Wandsworth, freeholds and twelve freehold building plots in Plaistow (where Wood had been living in 1861).

Obviously there are possibilities for further research on that score. There are other mysteries too. In all the examples I have seen, Wood appears as the publisher, but there are no credits given anywhere to artists, designers or engravers. Wood generally described himself as a publisher or stationer, occasionally as an embosser, but never as an artist of any kind, so we are at a loss to know who is responsible for the design of any of this material. The only print I know which names anyone other than Wood is a topical view in the British Museum of the William IV statue at the foot of King William Street (erected 1844), which adds the information, ‘J. Windsor, Card Maker, Meredith Street, Clerkenwell’. This is John Abraham Windsor, enamelled card manufacturer, and a man who did well through the association. In 1861 he was employing thirty men, as well as five boys and girls.

I imagine the connection lasted through most of Wood’s career. A court case brought by Wood in 1874 against Windsor’s son, William Joseph Windsor, presumably relates to some current trade dispute. And here is another line of research, for in the teasing catalogue entry of the bill in the National Archives, it is stated that the plaintiffs were ‘Joseph Thomas Wood (a person of unsound mind, not so found) by Elizabeth Mary Wood his next friend’. Too little time to get to Kew to check this, but someone perhaps should. Elizabeth Mary Wood was his widowed daughter-in-law, the Elizabeth Mary Holiday who had married his son, Joseph Robert, in 1860. She was herself described as a stationer on the 1871 Census, so clearly had some involvement with the business. She may well have been the plaintiff in Wood v Trevillion and her own son, Joseph Charles Wood (1863-1923), became a stationer, so it was perhaps he who eventually continued the business in a quiet way. Elizabeth herself, who died in 1915, lived on a private income, presumably deriving from Wood’s estate.

Lots more work for someone to do, but J. T. Wood is now at least partially rescued from a prolonged period of neglect. Given the size of his business, the breadth, ubiquity and distinctiveness of his output, as well as his extensive advertising, J. T. Wood must surely have been almost a household name in Victorian England.

The browned ‘glazed’ card looks like one of the ‘cartes en porcelaine’ which I used to come across when dealing in old postcards in Brussels in the 1970s. They were beautifully produced objects, mostly from the mid-nineteenth century, used for commercial advertising by local firms. They were much sought after by collectors, and I should imagine are now scarce. I mainly remember the Belgian items, but I seem to recall others from different European countries. I don’t recall seeing any from Britain. I believe they were manufactured using a process involving finely ground porcelain that was extremely hazardous for the unfortunate workers. Do you have any more information about them?

Regards,

Tim Johnston

LikeLike

I have just aquired a hand coloured engraving of Tom Cribb the World Champion Bareknuckle Boxer by J.T.Wood London I assume one and the same man have you any evidance that wood did such work

Best Regards

H. Eastwood

LikeLike

Interesting, John Abraham Windsor is a gt gt gt grandfather of mine.

LikeLike

I own a printing company and collect antique and vintage printing equipment, do you have any knowledge of what equipment was used to produce the valentines and memorial embossed/die cut cards. I have a collection of a few cards and their detail and quality amazes me even though produced in mid 19th century. Any info would be appreciated.

Thank you

phil.eldridge@btinternet.com

LikeLike

Pingback: Victorian Opulence | The Bookhunter on Safari

I have two works by Wood, one shows the “Crystal Palace – Exhibition 1851” and one the “Hungerford Suspension Bridge || Le Vont de Suspension au Hungerford à Londres”. The Bridge is from his adress at 33 Holywell Street, the Crystal Palace is exactly the same in size and look, but there is not his name on it. Instead there is written “Azulay, sc.”. That could be Bondy Azulay, famous for his Thames Tunnel paper peepshow. But I don’t understand what he has to do with the engraving of the Crystal Palace and why it is not from Wood, it really looks exactly the same as all the other enameled cards by him.

LikeLike

Hi, I have been writing up and re-researching the information i hold on my 4x great uncle J.T.Wood (yes this one) and have found your article very interesting. His parents were actually Robert Wood b, abt 1779 and Ann Elizabeth Shaner, b, abt 1788 and he was one of 6, the 2nd oldest. The profile I am putting together for him is here https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Wood-45367

LikeLike

A London Gazette entry for 3 July 1885 p. 3082 indicates the dissolution of a partnership between William Ben Simmons and John Frank Simmons ‘in the trade or business of Wholesale Stationers and of Fancy Printing and Embossing Stationery carried on at No. 278 Strand and No. 7 Crawford Passage, Farringdon Street…under the style of J.T.Wood & Co.’ and the continuation of the business by John Frank Simmons at Farringdon Street.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent. Thank you for this – that adds a great deal to what we know.

LikeLike

Our Society has 53 of these cards, most in excellent condition, in case anyone is interested in their acquisition. Most of the subjects are London establishments.

LikeLike