Fifty years ago — 1971 — the year I stumbled, almost by accident, into becoming a bookseller. I’ll tell you how in a future post, but it was not — on the face of it — a particularly auspicious time to start out. The year began badly with the Ibrox Disaster and the death of sixty-six football fans on the 2nd January — it was a world of crumbling and neglected infrastructure. A world too of loss of prestige: Rolls-Royce, that once shining symbol of British engineering excellence and know-how, went bankrupt on 4th February.

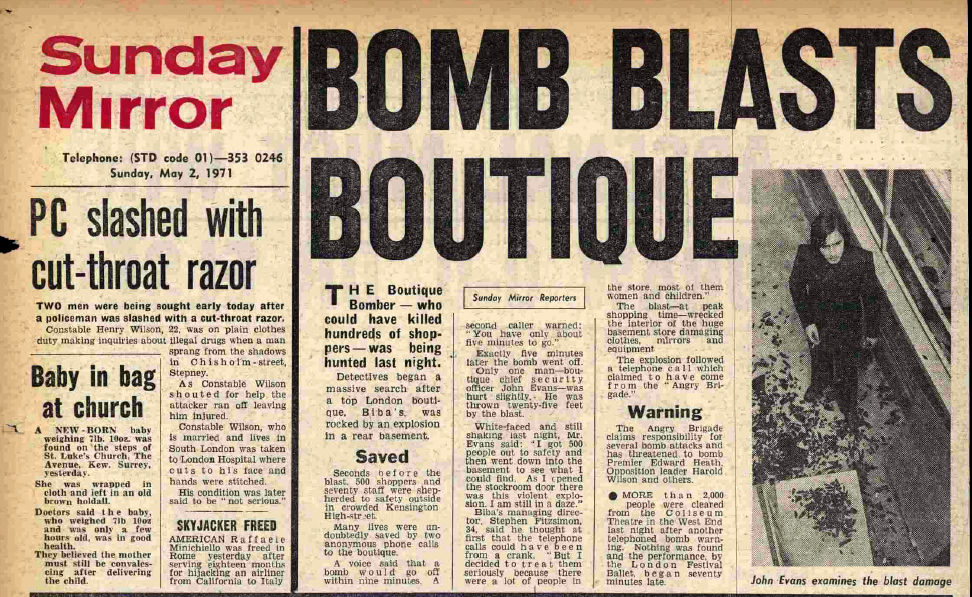

Sunday Mirror, 2nd May 1971. © The British Library Board.

The Angry Brigade commenced the year by bombing the home of Employment Secretary, Robert Carr, on 12th January, the latest in a spate of similar attacks. Later in the year the Brigade bombed Biba, the ultra-fashionable Kensington boutique, and in October claimed responsibility for bombing the Post Office Tower (the BT Tower). The IRA also claimed that particular bomb: if so, it presaged the start of a twenty-five-year campaign of mainland bombing. Just to note those closest to home: Cannon Street Station bombed in 1976, just a minute or two from my Cullum Street shop; a customer whom I’d seen a day or two earlier, a war-hero, blown to bits in his car in 1979; the Stock Exchange bomb in 1990 — literally just across the street from my Royal Exchange shop; and Bishopsgate in 1993 — big enough and close enough to blow out my shop-windows.

Endless strife, strikes and industrial action of one kind or another were also a feature of those years. A postal strike began on the 20th January 1971 — no mail for forty-seven days in an era when physical mail was as important as e-mail is now, actually more so, with so many transactions requiring cheques and documents in the post.

A year of protests, in particular against the Industrial Relations Act. Dissent of a different kind was punished by the prison sentences (quashed on appeal) imposed on Mick Jagger and Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones for very minor drug offences, as well as the six-week long obscenity trial inflicted on the publishers of Oz magazine — sentences again overturned on appeal. Meanwhile, Margaret Thatcher earned her “Milk-Snatcher” soubriquet by ending free school milk for the over-sevens.

A self-inflicted wound was the adoption of the new decimal currency on 15th February 1971. That stable, nuanced and highly sophisticated currency system of pounds, shillings and pence, perfectly adapted over a thousand years to the needs of a trading nation, was abolished in a moment — for a new currency in which nothing would divide by even such an ordinary and everyday low number as three without resorting to an infinity of decimal places. It was supposedly a superior system — but as Orwell once noted, “One has to belong to the intelligentsia to believe things like that: no ordinary man could be such a fool”. If units of ten are so superior, you might ask why we don’t use them for grown-up things — like measuring time, or hexadecimal computer code, or geometry — remind me again what the decimal equivalent of π is. Or simply remind me again why things are still boxed in dozens.

Economists are endlessly unwilling to admit that the introduction of this shiny and progressive new currency was the principal cause of the runaway inflation of the next decade. Depending on political viewpoint they blame militant unions, strikes and strikers, the oil crisis, the three-day week, failures of monetary policy, systemic lack of productivity, the decision to join the European Economic Community, the introduction of the gangrenous Value Added Tax (VAT) — and in some degree and in their interplay these certainly all played a part.

But almost all of these things happened after 1971 and the truth (for those of us who were there) was that if you abolish the smaller units of currency — pennies, threepenny bits, tanners, half-crowns and ten-shilling notes all went — then prices have nowhere to go but up to larger units. All the day-to-day transactions of ordinary life — a loaf of bread, a dozen eggs, a meal out, a cinema ticket, a gallon of petrol, a packet of cigarettes, a new paperback (none of these things cost anywhere near a pound in those days) — had previously been conducted in shillings. Its decimal equivalent — the new 5p coin — sounded as if it was worth a little less than the old sixpence (2½p). Very soon it was. Prices of ordinary things — a cup of tea or a newspaper — virtually doubled overnight.

The price of the average house was something under £5,000 in 1971. Ten years later it was close on £25,000 — and the price of almost everything else had quadrupled over the decade. I’m currently putting together a catalogue of books published in 1971 to try to recapture the spirit and feel of the time. Those published at the beginning of the year are priced in both pre- and post-decimal prices — those published later in the year in decimal alone — and were already costing noticeably more.

Unemployment hit a post-war high of close on a million in April. Strikes continued and over the winter there were lengthy power-cuts too. I vividly remember that it was by candlelight in the middle of a power-cut that I bought my first “expensive” book. The price means little enough now, but at the time it represented a full quarter’s rent on the shop — or enough to pay an assistant for three or four months. I can recall a slight tremor of the hand as I wrote out the cheque — or perhaps it was just the flickering of the candle.

In late October, the House of Commons voted in favour of joining the European Economic Community, or the Common Market as it was generally known — the precursor of the European Union. The Treaty of Accession was signed in January 1972 and the United Kingdom’s membership came into effect on 1st January 1973. In divisive times, few things were, or remained, so divisive — but in the real world the decision could never be wholly a good one or wholly a bad one — there were always going to swings and roundabouts. Correlation and causation are probably now too tangled to unravel, but the immediate chronology is plain enough in the official figures.

The value of shares on the UK Stock Market fell by 73% between 1st May 1972 and 13th December 1974 — larger losses than those sustained during either World War or the Great Depression. In 1973, the wider UK economy slipped into a deep double-dip recession from which it took fourteen quarters to emerge — for me at least the second-worst recession of my years in the book trade.

In 1971 British steel production had reached an all-time high — this was my father’s trade: we knew it inside out. “The 1971 census of employment recorded 323,000 steel workers, representing 1.5% of all in employment. By 1981 this had almost halved to 167,000 (0.8%)” (ONS website) — a reduction mirrored in greater or lesser degree across the entire manufacturing sector. In 1971, the UK balance of trade in goods and services stood in modest surplus. By the end of 1974 it was well into deficit, reaching an all-time record of 4.4% of our entire GDP. Even in the worst of the years that followed (and there were many) that deficit never again exceeded 3% of GDP (ONS website).

In the following year, in a theoretically almost impossible combination of deep recession and raging inflation, the annual inflation rate rose to somewhere close to 25%. It was announced in the House of Commons on 30th January 1976 that “Today the bankruptcy figures are higher than they have ever been since figures were first recorded in 1914” (part of a fascinating debate on the rapidly escalating problems of the self-employed and small business). By 1978, unemployment stood at a new post-war high of 1,500,000. Bank base rate was 5% in the autumn of 1971, when I began — and although the figure went up and down it stood at 9% by the end of 1972, 13% by the end of 1973, touched 15% in 1976, and then 17% in 1979.

In March 1976, the new Prime Minister James Callaghan was forced to call on the International Monetary Fund for a multi-billion-pound bail-out to rescue the country. Lots of clever people simply left — “In the mid-1970s, I joined the brain drain, and left Britain for America. Two of my close university friends went too. The decision to leave home required little thought. The trade unions seemed to be running the place. Inflation was making money worthless. The top rate of income tax was 83% — and if you were dim enough to invest in British business, creating jobs and enterprise, you paid an extra 15% ‘unearned income’ surtax, taking your tax rate to 98%” (Eamonn Butler, writing in 2011).

All in all, 1971 should not have been the best of times to start up in business — but strangely somehow it was. Everything was still cheap — rents and rates, utility bills, postage, and eating out of an evening. Regulation, even if only for a few short years, was still relatively light.

Culture — and indeed counter-culture — was vibrant. At the cinema we had Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange; Peter Bogdanovich and The Last Picture Show; Dirty Harry; The French Connection; Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs; Visconti’s Death in Venice; Klute; Shaft; Sunday Bloody Sunday; Nicolas Roeg’s haunting Walkabout, with a young Jenny Agutter; the latest Bond, Diamonds are Forever; Clint Eastwood’s disturbing Play Misty for Me; Ken Russell’s The Devils, with Vanessa Redgrave and Oliver Reed; those British classics, Gumshoe, with Albert Finney, Billie Whitelaw and Frank Finlay, and Get Carter, with Michael Caine, Ian Hendry, Britt Ekland, and a powerful cameo from playwright John Osborne; Richard Burton, Elizabeth Taylor and Peter O’Toole in Under Milk Wood; Joseph Losey’s The Go-Between; Twiggy in Ken Russell’s much under-rated The Boyfriend; and even Frankie Howerd in Up Pompeii.

The books of 1971 I shall leave for later post, but the West End Theatre of that year saw Harold Pinter’s Old Times at the Aldwych, directed by Peter Hall, with Colin Blakely, Dorothy Tutin and Vivien Merchant; Osborne’s West of Suez with Ralph Richardson and Jill Bennett; Simon Gray’s astonishing Butley, with Alan Bates, at the Criterion — all three of which I’m fairly sure I saw at the time (tickets in the gods for a few shillings), as well as an interminable production of Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey into Night with Olivier — and for other tastes there were Edward Bond’s bloody Lear at the Royal Court; Godspell at the Roundhouse (with both David Essex and Jeremy Irons in the cast), and No Sex Please, We’re British, which opened in June and ran for years.

Andy Warhol was in London in February for the opening of his full-scale exhibition at the Tate (there were also his drawings at the ICA and prints at the Mayfair), as well as Polaroids at the freshly launched Photographers’ Gallery. Later in the year, the Tate featured Eduardo Paolozzi, but it was the Robert Morris exhibition of interactive sculptural forms in May that grabbed the headlines. It was shut down just four days into a scheduled five-week run: the “over-zealous participation in the exhibition by some of our more exuberant visitors has resulted in excessive wear and tear” — wear and tear both on themselves and the exhibits — sprained fingers, torn muscles, a raft of splinters. The exhibition was recreated at Tate Modern in 2009, but without similar incident — exuberance had presumably got lost somewhere in the intervening years. Later in 1971 there were more sedate but fine exhibitions of both Constable and Hogarth — I think I still have the Hogarth catalogue somewhere.

At the ICA, the year began with AAARGH! A Celebration of Comics, followed by Edward Meneeley in March, and Picasso in London: A Tribute on his 90th Birthday in October. The relatively new Hayward Gallery offered a mixed bag: Art in Revolution: Soviet Art and Design since 1917; Tantra, the Indian cult of ecstasy, and a particularly memorable Bridget Riley retrospective — the first contemporary artist to have a full-scale exhibition there. At the Whitechapel Gallery there was Salvador Dali, Art-in-Jewels, and Gilbert & George a month later, the latter becoming occasional visitors to my shop in the years to come.

As for popular music, David Hepworth’s 1971 : Never a Dull Moment tells the story — “1971 saw the release of more monumental albums than any year before or since … January that year fired the gun on an unrepeatable surge of creativity, technological innovation, blissful ignorance, naked ambition and outrageous good fortune. By December rock had exploded into the mainstream. How did it happen? This book tells you how. It’s the story of 1971, Rock’s golden year”.

There was a kind of innocence in all this, difficult now to recapture. What made it an ideal time to start out was that business still worked largely on trust. Shops would accept a cheque if you were willing to write an address on the back — no-one ever asked for identification. Rents, both on shops and flats, were unimaginably cheap — and could very often be paid in arrears. In Cullum Street in the 1970s I had each full quarter to make some money before having to pay the rent. No-one at Hodgson’s, the book-auctioneers in Chancery Lane, ever quibbled about giving me — young and unknown as I was — thirty days’ credit to pay for my purchases. The firm had already been taken over by Sotheby’s, so my credit was good there too — and when in a tidying-up exercise a few years later it was decided that a more formal arrangement with a notional cap would be in order, the figure proffered was £10,000 a month — you could still buy a house for that.

The last sale at Hodgson’s, 1981. John Maggs, Eric Barton and Keith Fletcher recognisable enough – myself (out of focus, top left), not so much. From Giles Mandelbrote, ed., Out of Print & into Profit (2006).

Local bank managers still had almost complete autonomy. Judgement of character, a look in the eye, and a gentleman’s hand-shake still won out over box-ticking exercises ordained by head office. “I admire you young people, trying to start out in business in this day and age”, said mine — in 1973 or 1974 — as he offered me a substantial and more or less completely unsecured loan to buy the best part of a houseful of books at an astonishingly generous interest rate.

Inflation was unutterably cruel to those living on savings or on a fixed income, and inexcusable as an instrument of policy, but it served as an unearned boon and a blessing to those paying off loans or buying speculatively. It was almost impossible to make a mistake in buying a book in those early years: over-priced in 1971 would have been cheap by 1973.

For me, it was the luckiest and most thrilling of times. To be continued …

Glad you moved on from economic woes – I was too young to worry about those – to the great cultural events of 1971 that felt so exciting. Is it the same for people in their 20s now?

LikeLike

I somehow doubt it – but what do old people know?

LikeLike