“Well — if no-one will give you a job, then you’ll just have to make one up”, said my father over the breakfast table to his seemingly unemployable son. A little harsh, but the fact was that the best part of a year after finishing my university degree I had yet to land a job. It wasn’t for lack of trying: I had applied for dozens and traipsed all over London hand-delivering speculative letters during the postal strike. But to no avail.

I didn’t really know quite what I wanted to do, beyond a reasonable certainty that books would somehow have to be involved. I was qualified enough, in so far as a good degree in English Language and Literature ever actually qualifies anyone for anything at all. It was an external degree from London University — I had spent my three years of study not in London, but at St. Clare’s Hall in Oxford. A slightly odd establishment. There were a small number of us studying for various London degrees, but the bulk of the students in those days were either well-bred (and well-heeled) young women studying for their A-levels, or overseas students learning or polishing their English. The latter were also mainly, although not exclusively, well-bred and well-heeled young women. For a rather shy young man from an all-male grammar school, it was all rather idyllic. But that’s another story for another time.

The tuition was good. Some of it in-house — the director, Professor Tony Knowland, was a recognised authority on Yeats — but most of it involved us wandering off to meet up with various tutors dotted around the various Oxford colleges — St. John’s for the Metaphysical Poets, I remember in particular — and somewhere else I cannot now recall for Milton and Paradise Lost, taught by an extraordinary old man as blind as Milton himself. The meaning is all in the sound, you have to read Milton out loud.

Some of the tutors came to us. One — for a course on the History of Literary Criticism — was a young American don called Rick Gekoski. Yes, that Rick Gekoski. Our paths met again some years later when he abandoned university life to become the most influential bookseller of my generation — certainly in the modern first editions field — and now a fine novelist himself. In more recent times, it was always a highlight of the week when Angus O’Neill and I took our London Rare Books School students over to meet him each summer. Always riveting to listen to, just as he was as my tutor all those years ago. I remember he once asked me to read out all or part of an essay I had written — in my “usual trenchant prose” — to my fellow students. I am not wholly sure to this day whether he regarded trenchancy as a good thing or not.

We seldom acknowledge just how much luck, chance, accident, happenstance — whatever we want to call it — plays a part in our lives. I had come very close to getting three jobs, all of which, but for luck, could easily have set me on a wholly different career path. On the strength of one of my finals papers (History of Language), Professor Randolph Quirk of UCL had invited me in to discuss joining his colossal survey of how English grammar actually worked — analysing thousands of texts in thirty different ways. Fascinating undoubtedly, but potentially mind-numbing too (and the salary was miserly). Nothing came of it and both I and the academic world were spared a most unsuitable attachment.

Getting into publishing had been the main thrust of my unsolicited and hand-delivered postal-strike approaches. I managed to get an interview for an editorial job with Penguin, out at their headquarters in Harmondsworth. I prepared by shaving off the hippy beard of my student days, having a proper haircut for the first time in years, polishing my shoes to a military splendour, and donning a sober and business-like suit and tie. When I turned up, the atmosphere was distinctly more casual than I had been expecting, but I was given a passage of rather raw prose to edit into shape for publication. Having finished, I was asked to wait. Eventually the verdict came back. Yes — I had done extremely well — the best attempt at editing that particular passage they had yet encountered. But, on the other hand, the existing editors (scruffy and unkempt for the most part) did not feel they would be at all comfortable working with someone so buttoned-up, strait-laced and conservative in attire. No job for me. In hindsight, another lucky escape from an even more unsuitable attachment — although the injustice still rankles.

The third job I didn’t quite get was with the owner of a small chain of bookshops — five or six shops selling new books in and around the City of London. He was looking to expand his range. The shops only stocked a very limited number of titles — the best-sellers of the day and the publishers’ current top recommendations. He was looking for a bookish person to feed in a wider range of titles which might appeal to his customers, the younger and less conventional ones in particular. Did I know anything about poetry?

We got on very well, until we hit the matter of salary. Like many a recent graduate, I had a wholly inflated notion of my actual worth in the real world. He was offering a little more than the University of London, it is true, but rather less than I was happy to pay my own first assistant a few months later. Many years later, I discovered by chance that George Newlands (McLaren Books) was the successful rival candidate. I don’t doubt for a moment that George was much the better choice.

But the seeds of an idea had been planted. If City Booksellers had been able to grow a chain of shops so rapidly, and if the other chains were all only stocking the same narrow range of titles (I’d had a car-crash of an interview with someone from W. H. Smith as well), then surely there must be scope for an independent bookshop offering a bit more variety. Perhaps just a little shop to begin with — mostly paperbacks. From my interviews I had rightly or wrongly gained the impression that publishers were then willing to offer a great deal of extended credit — six months to pay — even books on sale or return. How hard could it be to make this viable?

It was fortunate that my father had started his own successful business a few years earlier. He had made up a job and so could I. With his encouragement, I began to look for some suitable premises for my paperback shop. And then, one evening, in the classified advertisement columns of the Evening Standard — I stumbled into the rarest of good fortune. I could so easily have missed it. A tiny two-line note of a second-hand bookshop for sale. Well, I thought, why not sell some second-hand books along with my paperbacks? I made an appointment to see the owners — just a fact-finding mission to see how the second-hand trade worked. At least so I imagined.

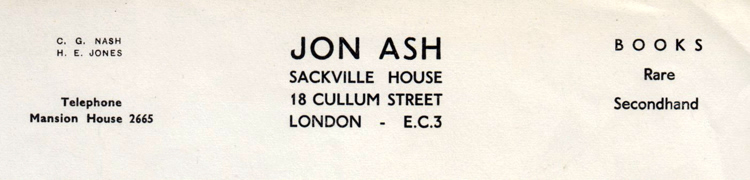

It became a date easy to remember. It was on my twenty-third birthday that I first met Hugh Ernest Jones (1895-1980) — on the right of the photograph — and Cyril Gordon Nash (1899-1982), on the left. They traded as “Jon Ash”, a topping-and-tailing of their names they had first used in a play they had written together before the war (set in a South London bookshop). Their shop in Cullum Street (between Fenchurch Street and Leadenhall Market) was a small one, not much more than a spacious cupboard with an odd hind-leg, the front window turned in on itself to face the passage into the shop rather than the street. The portion of the window actually fronting the street was just twenty-three inches (58cm) across. I walked right past it without seeing it the first time.

Inside, teetering piles of books on their sides, rows deep in places, mostly facing inwards rendering the titles invisible. These effectively hid almost all of the actual book-shelves behind them. In the middle there was an ocean of old maps and prints, housed in folders made of old Admiralty charts. After chatting to these two affable but slightly cagey old gents for a while, I found myself saying, “Let me get this straight. You are only open five days a week, Monday to Friday — and your opening hours are just from twelve o’clock until two o’clock — two hours a day?” — “Yes, yes”, they replied, “There’s only a lunch-time trade around here and we need to leave at two to catch the train”.

Pressed further, they confirmed that they had both been making a decent living out of the business since 1946 — and they were able to pay Alice (who guarded the till) something as well. They dealt mainly in second-hand books, but had some rare books too. One of them plucked a pinkish book from the nearest pile, blew some dust off it, and said, “Here’s an Oscar Wilde first edition”. It was still priced in shillings. I was utterly enchanted.

I had spent hours in the second-hand bookshops of Oxford looking for student texts, but of the world of rare books I knew nothing at all. Nothing whatsoever. But this is what I was born to do. The books were already priced (albeit still in shillings and pence), and at least I could extend the opening hours — eleven until three sounded reasonable — tidy the place up, set the books straight, and get busy with hoover, duster and Windolene. Two days later, I went back to Cullum Street and made an offer: their asking price could presumably be negotiated down quite considerably — but I would meet it in full and without quibble. Although only on the basis of paying part of it now (funded by my father, nominally in the form of a loan), and the rest over the next five years. The partners conferred. A couple of other people had been interested, but after a year of trying to sell up, this was the first firm offer they had received. My luck was in. We shook hands — I had become a bookseller, and Hugh and Cyril my mentors.

To be continued …

Mr Nash was the one that I remember: I bought several prints from the Microcosm from Jon Ash, and much else besides, when I was working as a broker in Lloyds next door. I thought that he was Jon Ash, and I don’t remember his partner. I now sell antiquarian books myself, and I have my own copy of the Microcosm……

LikeLike

Thank you. Yes, Hugh Jones was always more of the outside man, attending auctions and so on. Even when in the shop, he usually left Cyril to do the talking.

LikeLike

A lovely story. I look forward to Episode 2.

LikeLike

Thank you. There is more to tell!

LikeLike