Frank Ford jacket for “Barmy in Wonderland” (1952).

No-one with even a passing interest in British twentieth-century first editions will fail to recognise the work of the artist and cartoonist Frank Ford, if only for the series of dust-jackets he produced for the fiction of P. G. Wodehouse either side of 1950 – a sustained sequence commencing with “Money in the Bank” in 1946 and ending with “Barmy in Wonderland” in 1952. The vibrant colour, the economy and verve of line, the theatrical expressions and the bold and confident boxy signature all make his work instantly identifiable. For all that, it was only a chance exchange with a new customer which led me to think a little bit further about him – a customer (and thank-you to him) attempting to collect books decorated with his less well-known dust-jackets. What a delightful notion, to build a whole collection of Ford jackets to be displayed together.

Postscript 2021 – There is now a display of all Ford’s known dust-jackets and book-covers elsewhere on the blog at A Frank Ford Gallery.

It is said that Ford’s work was much influenced by the American “New Yorker” school and there is some truth in that, but this is a very British style, showing at least as much affinity with the world of the saucy seaside postcard as anything more exotic. It is a world of chinless wonders and innocents abroad, Colonel Blimps and rubicund majors, horrifying aunts, portly clerics, imperious butlers, decent chaps with pipes, not-so-dumb blondes, and flash types with dodgy moustaches. A friendly and familiar world of stereotypes and just perfect for

It is said that Ford’s work was much influenced by the American “New Yorker” school and there is some truth in that, but this is a very British style, showing at least as much affinity with the world of the saucy seaside postcard as anything more exotic. It is a world of chinless wonders and innocents abroad, Colonel Blimps and rubicund majors, horrifying aunts, portly clerics, imperious butlers, decent chaps with pipes, not-so-dumb blondes, and flash types with dodgy moustaches. A friendly and familiar world of stereotypes and just perfect for

“Ow often must I tell ’im about ’is tone values?” From “You Needn’t Laugh” (1935).

Wodehouse – a world in which we don’t take ourselves too seriously and all-too-human foibles are treated with affection and a generosity of spirit – although Ford’s cartoons can also have a subversive, or at least a self-deprecating, edge – the neat role reversal of the nude model herself painting the artist in a silly pose – or the delightful Cockney char who tidies up the artist’s paintings as well as his studio – “Ow often must I tell ’im about ’is tone values?”

Frank Ford jacket for “Joy in the Morning” (1947).

What I didn’t expect about such a familiar figure was that there should be such a dearth of reliable information about him. I searched reference books and the internet in vain for something more substantial than a short statement about his period of activity and some brief examples of the work. There is no mention of him at all on the British Cartoon Archive website, which seems to be an extraordinary lapse. He didn’t prove easy to track down, but luck and serendipity played their part.

Frank Wallis Ford (1906-1970) was born on 28th June 1906 at Hurstbourne Road, Forest Hill, in South London, the elder of the two sons of Harry Cecil Ford (1875-1917), a clerk to a firm of brokers in pearls and precious stones, later killed in action on the Western Front, and his wife, the Peckham-born Cecilia

Frank Ford jacket for “Full Moon” (1947).

Hunter Keeler (1875-1964). Ford’s parents had been married in 1904 and by 1911, the family, now enlarged by the birth of his younger brother, Geoffrey Ford (1909-1976), were living at 69 Silverdale, between Sydenham Station and Sydenham Recreation Ground (now known as Mayow Park). After his father’s death, the family moved to the eastern suburbs and Ford was educated at Chigwell School.

There was an artistic streak in the family – the children’s author and illustrator Priscilla Mary Warner, née Ellingford, (1905-1994) was a first cousin on his mother’s side – and after leaving school, Ford studied for a time at Bournemouth Art College. He is then reported to have worked for the giant publishing house of C. Arthur Pearson Ltd., but by the age of twenty his independent cartoons were already being regularly accepted for publication by “The Bystander”.

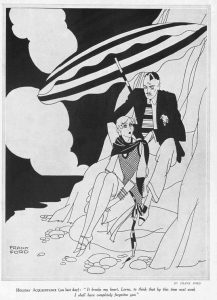

“It breaks my heart, Lorna …”. From “The Bystander”, 31st July 1929. © Illustrated London News Group. Image courtesy of The British Library Board.

His work evolved rapidly in style, the earliest of it barely distinguishable from the kind of thing that had been appearing in “Punch” for years, but soon developing via the occasional almost Beardsley-like elaboration into a recognisable art deco phase – razor-sharp renditions of flappers and their beaux in dramatic black-and-white – and from there, through an increasing economy of line, into his own highly individual style. The humour could be sharp too – a holiday romance abruptly ends in 1929 with the words, “It breaks my heart, Lorna, to think that by this time next week I shall have completely forgotten you”. His double-page spreads of social types under such headings as “Public Enemies” and “Better Uninvited” – caricatures of the Aesthete, the Balloon Burster, the Buttonholer, the Coy-Maker, the Mistletoe Fiend, the Raconteur, the Wet Blanket, and all the other types best avoided at parties – are a particular joy, as are the limericks of his “Weeds from Poetry’s Garden” sequence.

A collection of his cartoons, some of which had previously appeared in “The Bystander”,  was published in a generous large format by Methuen in 1935 under the title “You Needn’t Laugh”, and by this stage he was also contributing to many of the other popular magazines of the day – “Lilliput”, “Passing Show”, “Punch”, “Strand”, “Tatler”, etc. He was also undertaking advertising work and occasional book illustration – illustrations, for example, for Alec Waugh’s “Eight Short Stories”, published by Cassell in 1937, and the British edition of “Why Should Penguins Fly?”, written by the really rather risqué American cabaret performer, Dwight Fiske, and published by Robert Hale, also in 1937. There is a splendid coloured Ford dust-jacket for the latter, if you can find one – and I’m told that the book was always strictly off-limits to Ford’s children.

was published in a generous large format by Methuen in 1935 under the title “You Needn’t Laugh”, and by this stage he was also contributing to many of the other popular magazines of the day – “Lilliput”, “Passing Show”, “Punch”, “Strand”, “Tatler”, etc. He was also undertaking advertising work and occasional book illustration – illustrations, for example, for Alec Waugh’s “Eight Short Stories”, published by Cassell in 1937, and the British edition of “Why Should Penguins Fly?”, written by the really rather risqué American cabaret performer, Dwight Fiske, and published by Robert Hale, also in 1937. There is a splendid coloured Ford dust-jacket for the latter, if you can find one – and I’m told that the book was always strictly off-limits to Ford’s children.

Frank Ford at war. Photograph courtesy of the Ford family.

In the spring of 1939, Ford joined the Territorial Army in anticipation of the coming war, subsequently becoming a lieutenant in the regular army’s 157th (Hants) Royal Armoured Corps. Posted to North Africa in 1942, his artistic skills were made good use of in the development of Montgomery’s inventive camouflage schemes and the brilliantly successful deceptive ploy involving dummy tanks, fake artillery, bases, dumps and pipelines. Ford even appears to have been seconded for a time to a wholly fictitious 101st Royal Tank Regiment as part of the overall deception. Having seen action in Egypt, Cyrenaica, Palestine and Syria, he returned to England in August 1944. After the cessation of hostilities, he then spent some time in Germany helping to deal with the colossal numbers of “displaced persons” – in his case Latvian ones –

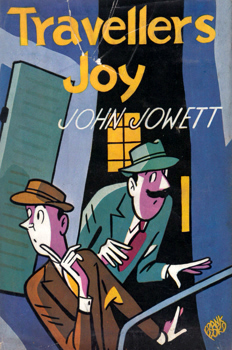

Frank Ford jacket for John Jowett’s “Travellers’ Joy” (1950).

Latvia having been ravaged by both the Nazis and the Soviets. No doubt aided by his gentle humour and the ability to play a “mean pub piano”, he made many friends. I am very much indebted to his family for information on this and many other points, as well as this photograph of Ford in action in the desert.*

In England once more, Ford resumed his former career. He also married Joan Burgoyne, née Rayner, (1916-1992), originally from Hampstead, at Bournemouth in 1947. His style now pared to utter simplicity of line and mass, in the years either side of 1950 Ford produced a good many dust-jackets for Herbert Jenkins Ltd. – not just the well-known Wodehouse titles already mentioned, but also fresh designs for reprints of earlier Wodehouse books and jackets for other authors from the stylish Jenkins stable of humourists – the now largely forgotten “John Glyder” (Allen George Roper, 1888-1957), John Aves Jowett (1921-1960), and others.

Frank & Geoffrey Ford, “Digby’s Holiday” (1951). Courtesy of the Ford family.

He also illustrated the now seemingly impossible-to-find children’s book, “Digby’s Holiday” (1951) – the story of a crane leaving its building site to have its own seaside holiday and causing mayhem – this, a particular favourite in his own family, was co-produced with his younger brother, Geoffrey Ford, who had himself earlier written “Hedgehog’s Holiday” (1938) and “Patsy Mouse” (1947) – both illustrated by Helen Haywood (1908-1995), creator of the “Peter Tiggywig” books, a skilled fore-edge painter, and a lifelong friend of Frank Ford and his family from his Bournemouth Art College days.

© Colnect.

Ford’s later activities concentrated rather more on his work in advertising (he was art-buyer for the Everett’s agency for some time). Some of us, those of a certain age, will very well remember the Fremlin’s Brewery “Elephant” campaign – Ford’s images of friendly elephants ubiquitous on buses, billboards, and beer-mats – and he also created posters for such events as the Toy Fair. His career subsequently wound down with the onset of angina, although he continued to produce the weekly “Minnie” cartoon series for “Woman’s Realm” from 1958 until his death in 1970. He died at the age of sixty-four on 28th July 1970 at Ashford Hospital near Staines.

“Which do you recommend for a whist drive?” From “Woman’s Realm”, 4th December 1965. Courtesy of the Ford family.

Mourning his death and the first ever issue of the magazine not to have a fresh “Minnie” cartoon, a colleague from “Woman’s Realm” remembered him and his old-school virtues in words that can hardly be bettered:

“Frank was our friend and we all loved him. People who met him casually took him for a jolly, breezy, light-hearted man. In fact, he was deeply sensitive, thoughtful and – like so many humourists – serious-minded and rather sad at heart about the silliness of the world.

Before his last illness, he had been twice in hospital, forbidden to work. He never said a word to us. He drew Minnie secretly under the bedclothes and had her smuggled out to the post. He was a professional and he never let us down.

Frank Wallis Ford (1906-1970). From “Woman’s Realm”, 19th September, 1970. Courtesy of the Ford family.

Quite recently, by chance, we discovered that he had been devoting a great deal of time to social work. He never talked about it. The truly good don’t advertise the good they do. He would have hated us to catalogue his virtues or to probe into this other work he did so self-effacingly. He is still entitled to his reticence. So we simply record our lasting affection and gratitude to a friend and colleague, and send our deepest sympathy to his wife and children”.

I am extremely grateful to those same children, Nick and Linden, for their incredibly generous help in putting together this snapshot of their father’s life.

*For both a more complete account of Ford’s wartime experiences and a case-study in the use of army records, there is an article by Nick Ford entitled “Tracing Frank’s War” in the May 2014 issue of “Your Family Tree” magazine, pp.42-44.

What an amazing amount of information you have unearthed in no time at all. I always thought from the kindly humanity of his jackets that he was one of the good guys – it is nice to have it confirmed. Well done! I hope this blog won’t send his jacket prices through the roof before I have completed my collection.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for this – we try to please. And let’s hope it produces some further examples for your collection. All best wishes, Laurence.

LikeLike

As a Yank unfamiliar with Ford, I truly enjoyed this. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Why thank you. Always good to know that the effort has been worthwhile.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for this amazingly detailed biography of Frank Ford. I have three of his designs for PG Wodehouse dust jackets – Bring on the Girls, Piccadilly Jim and Doctor Sally. Piccadilly Jim is completely typical of the style illustrated in your article. If I had the technology I’d attach a picture of it but getting from my mobile phone to here is beyond me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think you’ll find that the jacket illustration for “Bring On The Girls” was a photograph of a chorus line.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Through my love for Wodehouse, I’ve recently become obsessed with his art! Is there a gallery of sorts of his illustrations? Boy, I wish there were an art book. Thanks!

LikeLike

Not that I know of – but you could start by making a Pinterest board!

LikeLike

I can send anyone who is interested what I believe to be a complete list of Frank Ford dust jackets, all Herbert Jenkins, 1948-52.

Michael House.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Laurence for the research and the article. Michael I should very much like a list of his dust jackets, please. I have made a list of 9 non Wodehouse titles so far but imagine there may well be many more. How do I get the list from you?

Thanks,

Ian.

LikeLike

Let me have your email address and I’l forward it. Let me know if you have found any I have missed. Michael.

LikeLike

Thank you to you both. A list would be very useful. I could even append it to the post, if you thought it worthwhile.

All best, Laurence.

LikeLike

Sure. I need to attach it to an email. Michael.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve set up a new email – FrankFordDJ@outlook.com. Please could you send your list there and I’ll send mine in return. I’m up to 12 now.

Ian.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: A Frank Ford Gallery | The Bookhunter on Safari